what incentives did the incas give local rulers to obey?

The centre of Inca ability was the upper-case letter Cuzco, considered the omphalos of the world. forty,000 Incas governed an empire of over 10 million subjects who spoke over 30 different languages. Consequently, the centralised government employed a vast network of local administrators who relied heavily on a combination of personal relations, state largesse, ritual exchange, constabulary enforcement and military might.

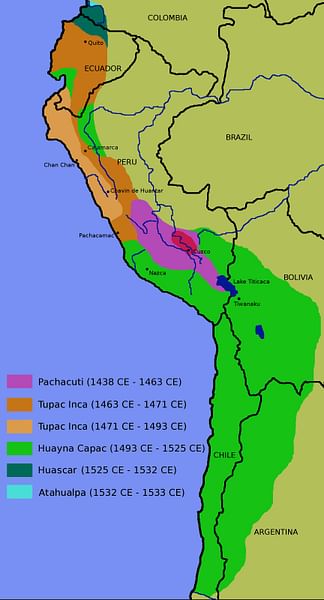

The system certainly worked and the Inca culture flourished in aboriginal Peru between c. 1400 and 1534 CE. The Inca empire eventually extended beyond western South America from Quito in the north to Santiago in the south, making it the largest empire always seen in the Americas.

Historical Overview – The Empire

Cuzco became a significant middle sometime at the beginning of the Belatedly Intermediate Period (k-1400 CE). A procedure of regional unification began from the late 14th century CE, and from the early 15th century CE, with the arrival of the get-go great Inca leader Pachacuti ('Reverser of the World'), the Incas began to expand in search of plunder and production resource, first to the south and then in all directions, then they built an empire which stretched across the Andes.

The rise of the Inca Empire was spectacularly quick. First, all speakers of the Inca language Quechua (or Runasimi) were given privileged status, and this noble form and then dominated all the important roles within the empire. Eventually a nationwide system of tax and administration was instigated which consolidated the power of Cuzco. The Incas themselves called their empire Tawantinsuyo (or Tahuantinsuyu) meaning 'Country of the Four Quarters'.

The Incas imposed their organized religion, administration, and even art on conquered peoples.

The Incas imposed their religion, assistants, and even fine art on conquered peoples, they extracted tribute, and even moved loyal populations (mitmaqs) to better integrate new territories into the empire. However, the Incas likewise brought certain benefits such equally food redistribution in times of environmental disaster, better storage facilities for foodstuffs, work via state-sponsored projects, state-sponsored religious feasts, roads, military assistance and luxury goods, especially fine art objects enjoyed by the local aristocracy.

The Inca King

The Incas kept lists of their hereditary kings (Sapa Inca, meaning Unique Inca) and then that we know of such names as Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui (reign c. 1438-63 CE), Thupa Inca Yupanqui (reign c. 1471-93 CE), and Wayna Qhapaq (the concluding pre-Hispanic ruler, reign c. 1493-1525 CE). It is possible that two kings ruled at the same time and that queens may have had some significant powers, but the Spanish records are not clear on both points. The king was expected to marry on his accession, his bride sometimes being his own sister. The queen (Qoya) was known every bit Mamancik or 'Our Mother' and could wield some influence both on her husband and via her kin group, particularly in selecting which son might become the official heir to the throne. The Qoya also had significant wealth of her own which she could dispose of as she wished.

The Sapa Inca was an absolute ruler whose word was law. He controlled politics, society, the empire'south food stores, and he was commander-in-master of the army. Revered as a god he was besides known as Intip Churin or 'Son of the Sunday'. Given this elevated status he lived a life of great opulence. Drinking from gilt and silver cups, wearing silver shoes, and living in a palace furnished with the finest textiles, he was pampered to the extreme. He was fifty-fifty looked afterward following his death as the Inca mummified their rulers and later 'consulted' them for their opinion on pressing country diplomacy. Despite his enviable status, though, the male monarch had to negotiate the consent and back up of his nobles who could, and did, sometimes depose or fifty-fifty electrocute their ruler. In addition to keeping favour with his nobles the king also had to perform his part as a magnanimous benefactor to his people, hence his other championship Huaccha Khoyaq or 'Lover and Benefactor of the Poor'.

Map of the inca Empire

The Inca Nobles

Inca dominion was, much like their famous architecture, based on compartmentalised and interlocking units. At the meridian was the king, his high priest (Willaq Umu) – who could as well deed equally a field marshal - and ten royal kindred groups of nobles called panaqa. These nobles could form and instigate policy in councils with the king and, even more importantly, influence the final choice of the king's successor which was rarely simply the eldest son. Indeed, many purple accessions were preceded past intrigue, political maneuvering, coups, and even assassinations to promote a particular kin grouping's candidate. This may well be why later Inca kings married their own sis and then as to avoid widening the elite ability base at the very top of the government structure.

Side by side in line to the panaqa came x more than kindred groups more distantly related to the king and divided into two halves: Upper and Lower Cuzco. And so came a third group of nobles non of Inca claret but fabricated Incas as a privilege. This latter group was drawn from that section of the population which had inhabited the region when the Incas had first arrived. Every bit all of these groups were composed of dissimilar family lines, there was a dandy deal of rivalry betwixt them which sometimes broke out into open warfare.

The Inca Administrators

At the bottom of the country apparatus were locally recruited administrators who oversaw settlements and the smallest Andean population unit of measurement the ayllu, which was a collection of households, typically of related families who worked an area of country, lived together, and provided common support in times of need. Each ayllu was governed by a pocket-size number of nobles or kurakas, a role which could include women.

Local administrators collaborated with and reported to over eighty regional-level administrators (a tokrikoq) who were responsible for such matters as justice, censuses, land redistribution, organizing mobile labour forces, and maintaining the vast network of roads and bridges in their jurisdiction. The regional administrators, who were almost always ethnic Incas, reported to a governor responsible for each quarter of the empire. The iv governors reported to the supreme Inca ruler in Cuzco. To ensure loyalty, the heirs of local rulers were also kept as well-kept prisoners at the Inca capital. The nearly important political, religious, and military roles within the empire were, then, kept in the hands of the Inca elite, called by the Spanish the orejones or 'big ears' because they wore large earspools to signal their status. To better ensure the control of this aristocracy over their subjects, garrisons dotted the empire and entirely new administrative centres were congenital, notably at Tambo Colorado, Huanuco Pampa and Hatun Xauxa.

Inca Qollqa

Taxation & Tribute

For tax purposes almanac censuses were regularly taken to continue track of births, deaths, marriages, and a worker'south status and abilities. For administrative purposes populations were divided up into groups based on multiples of ten (Inca mathematics was about identical to the organization we use today), fifty-fifty if this method did not always fit the local reality. These censuses and the officials themselves were examined every few years, along with provincial diplomacy in general, by defended and independent inspectors, known as a tokoyrikoq or 'he who sees all'.

Equally at that place was no currency in the Inca world taxes were paid in kind - normally foodstuffs (specially maize, potatoes, and dried meat), precious metals, wool, cotton wool, textiles, exotic feathers, dyes, and spondylus shell - but also in labourers who could exist shifted about the empire to exist used where they were most needed. This labour service was known as mit'a. Agricultural state and herds were divided into iii parts: production for the state religion and the gods, for the Inca ruler, and for the farmers' own apply. Local communities were too expected to assistance build and maintain such imperial projects as the road organisation which stretched beyond the empire. To keep rails of all these statistics the Inca used the quipu, a sophisticated assembly of knots and strings which was also highly transportable and could tape decimals up to 10,000.

Goods were transported across the empire along purpose-congenital roads using llamas and porters (there were no wheeled vehicles). The Inca road network covered over 40,000 km and too as assuasive for the like shooting fish in a barrel motility of armies, administrators, and trade goods it was also a very powerful visual symbol of Inca authorisation over their empire.

Collapse

The Inca Empire was founded on, and maintained, by force and then the ruling Incas were very oftentimes unpopular with their subjects (especially in the northern territories), a situation that the Spanish conquistadores, led by Francisco Pizarro, would take full advantage of in the middle decades of the 16th century CE. Rebellions were rife, and the Incas were actively engaged in a war in Ecuador, where a second Inca uppercase had been established at Quito, just at the time when the empire faced its greatest ever threat. Likewise hit by devastating diseases brought by the Europeans and which had actually spread from Central America faster than their Quondam World carriers, this combination of factors would bring nearly the collapse of the mighty Inca civilization before it had fifty-fifty had risk to fully mature.

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to bookish standards prior to publication.

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/Inca_Government/

0 Response to "what incentives did the incas give local rulers to obey?"

Enregistrer un commentaire